What we’ve learned about screening for safety net services in Richmond

Everyone we met in Richmond wants to get uninsured patients into primary care and avoid preventable ER visits, and Richmond has a network of free and low-cost clinics run by incredibly dedicated staff. Still, both patients and providers told us that the time and effort required to get an appointment discourages many people from using those services. Funding and clinical capacity are certainly part of the reason for wait times, but we also heard that the application process itself was often slow and frustrating for everyone involved. This stood out as an area where we might be able to help, so we spent much of our last visit interviewing people who work on screening, and even got staff from half a dozen service providers together to brainstorm. Here’s what we’ve learned so far.

Who’s eligible for discounted care?

This is what the health insurance landscape looks like in Virginia for low income people without employer-based insurance.

Because Virginia chose not to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, people with incomes in the blank area above still don’t have affordable insurance options, and some who qualify for subsidized marketplace plans still find the cost out of reach. Richmond also has a significant number of undocumented immigrants who aren’t eligible for any of the options above. Most charity care is aimed at people in these groups, who can’t get insurance and would otherwise have to pay full price out of pocket.

In order to focus limited resources on those who need it most, almost all safety net providers have a screening process that determines whether a patient is eligible for free or discounted care (the exception is Care-A-Van, a Bon Secours mobile clinic program). Often, the organization’s funders shape the eligibility criteria and conduct audits, so it’s important to document the decision.

What kind of information do applications ask for?

Income

Providers ask for the patient’s household size and household income and use this to calculate her income as a percentage of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), then compare this to the organization’s cut-off or sliding scale. Asking someone for their household size and income sounds like it should be simple, but there are usually dozens of related questions. Some are used mostly to help staff determine if the answers are consistent. For example, if someone reports a very low income but doesn’t have a high food stamp allotment, it could indicate that something’s off. There are also subtly different ways of wording the questions, which could mean the same person answering differently on two forms. For example, the federal definition of “household size” is essentially the number of tax filers plus the number of dependents, but providers try to translate this for people who might not file taxes or might have lower literacy levels. As a result, one form says “people you are financially responsible for” while another says “family members in house.”

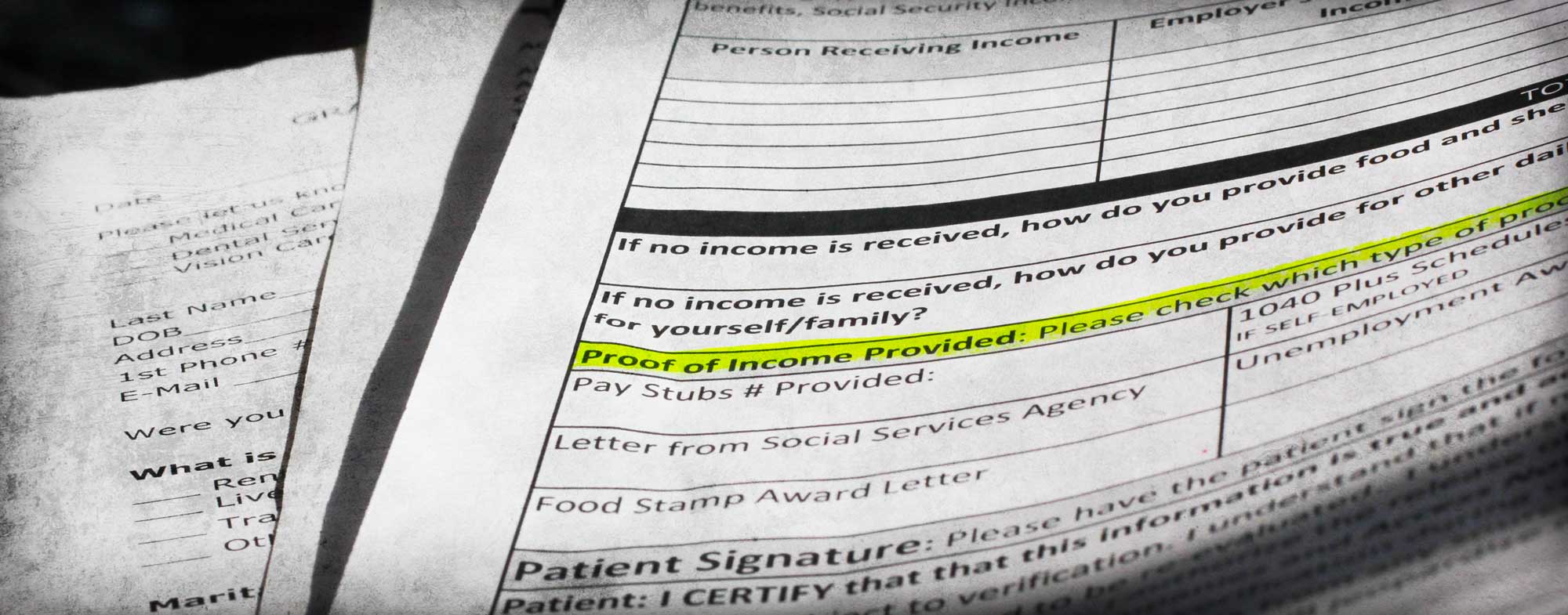

Income documentation

Screening usually requires patients to show documents that prove their income. This is really the most fundamental requirement (a Code for America team working on an alternative food stamp application process in California decided to eliminate income questions entirely, since they can infer the answers from the income documentation). Pay stubs are the most common choice, but they can be tricky. Sometimes patients haven’t kept two months’ worth of pay stubs because they didn’t think they would need them. Some people don’t have pay stubs because they’re paid under the table. Others work inconsistent hours, so their pay varies widely. Patients can also ask their employers for a letter stating their wages, but some employers won’t do that, especially if they hired the patient illegally. If you don’t have any income, you often need a notarized letter from someone who supports you (some services have notary publics on staff, making this easier than we initially imagined). Services work with patients to find something that makes sense--for example, some will accept a signed self-declaration of income if other options are unavailable--but it’s often a long process. Some providers use third-party systems like Experian or the Virginia Employment Commission to double-check patients’ employment or income, but they still ask patients to provide documentation.

Insurance eligibility

Providers want to encourage patients who are eligible for insurance to use those benefits rather than charity care, so it’s important to check whether a patient currently has insurance or might qualify for government programs. The requirements can be so complicated, though, that this isn’t always an easy question to answer.

How does the screening process work right now?

It can be slow and confusing

No two organizations screen in exactly the same way, but here’s an example of a screening process at one primary care clinic: