Executive Summary

We want to make it easier to apply for safety-net healthcare services.

The City of Richmond and our community partners asked our fellowship team to focus on healthcare services for low-income residents. More than a quarter of Richmond residents live in poverty, and many do not have health insurance. They depend on a network of public and private organizations that provide free or discounted care to the uninsured. During our first month in Richmond, we met with clinic and hospital staff, patients, researchers, and community organizations. Everyone wants to help patients get primary care and reduce unnecessary emergency department (ED) visits, but we heard that for many people, going to the ED is a better option than primary care. The ED is always open, patients are seen right away, and payment isn’t required up front. Primary care clinics, on the other hand, often have a confusing eligibility screening process and long waits for appointments.

We think technology can make the eligibility screening process easier and more efficient. With the input of potential users in Richmond, we’re building a web application that allows patients to apply for safety-net health services online and helps organizations share this information to reduce redundant screenings.

Team

Emma Smithayer

Fellow

Software Engineer

Sam Matthews

Fellow

GIS Analyst

Ben Golder

Fellow

Designer

Danny Avula

Deputy Director

Richmond City Health District

Andreas Addison

Civic Innovator

City of Richmond

Partners

Focus Area

Background

This is what the health insurance landscape looks like in Virginia for low-income people without employer-based insurance.

Because Virginia did not expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, people with incomes in the blank area above still don’t have affordable insurance options, and some who qualify for subsidized marketplace plans still find the cost out of reach. Richmond also has a significant number of undocumented immigrants who aren’t eligible for any of the options above.

Richmond's network of low-cost clinics and care programs do great work caring for patients without insurance. But both patients and providers told us that the time and effort required to get an appointment discourages many people from using those services. Funding and clinical capacity are certainly part of the reason for wait times, but we also heard that the application process itself was often slow and frustrating for everyone involved. In order to focus limited resources on those who need it most, the application process at almost all safety net providers includes an eligibility screening that determines whether a patient meets the criteria for free or discounted care (the exception is Care-A-Van, a Bon Secours mobile clinic program). Often, the organization’s funders shape the eligibility criteria and conduct audits, so it’s important to document the decision.

How Eligibility Screening Works

What kind of information do applications ask for?

- Income: Providers ask for the patient’s household size and household income and use this to calculate their income as a percentage of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), then compare this to the organization’s cut-off or sliding scale. Asking someone for their household size and income sounds like it should be simple, but there are usually dozens of related questions. Some are used mostly to help staff determine if the answers are consistent. For example, if someone reports a very low income but doesn’t have a high food stamp allotment, it could indicate that another income source is missing. There are also subtly different ways of wording the questions, which could mean the same person answers it differently on two forms. For example, the federal definition of “household size” is essentially the number of tax filers plus the number of dependents, but providers try to translate this for people who might not file taxes or might have lower literacy levels. As a result, one form says “people you are financially responsible for” while another says “family members in house.”

- Income documentation: Screening usually requires patients to show documents that prove their income. This is really the most fundamental requirement (a Code for America team working on an alternative food stamp application process in California decided to eliminate income questions entirely, since they can infer the answers from the income documentation). Pay stubs are the most common choice, but they can be tricky. Sometimes patients haven’t kept two months’ worth of pay stubs because they didn’t think they would need them. Some people don’t have pay stubs because they’re paid under the table. Others work inconsistent hours, so their pay varies widely. Patients can also ask their employers for a letter stating their wages, but some employers will refuse, especially if they hired the patient illegally. If a patient has no income, he often needs a notarized letter from someone who supports him (some services have notary publics on staff, making this easier than we initially imagined). Services work with patients to find something that makes sense (for example, some will accept a signed self-declaration of income if other options are unavailable), but it can be a long process. Some providers use third-party systems like Experian or the Virginia Employment Commission to double-check patients’ employment or income, but they still ask patients to provide documentation.

- Insurance eligibility: Providers want to encourage patients who are eligible for insurance to use those benefits, so it’s important to check whether a patient currently has insurance or might qualify for government programs. The requirements can be so complicated, though, that this is not always an easy question to answer.

- Demographic information: Some forms also include demographic questions for grant application purposes. These often vary widely among organizations.

How does the screening process work?

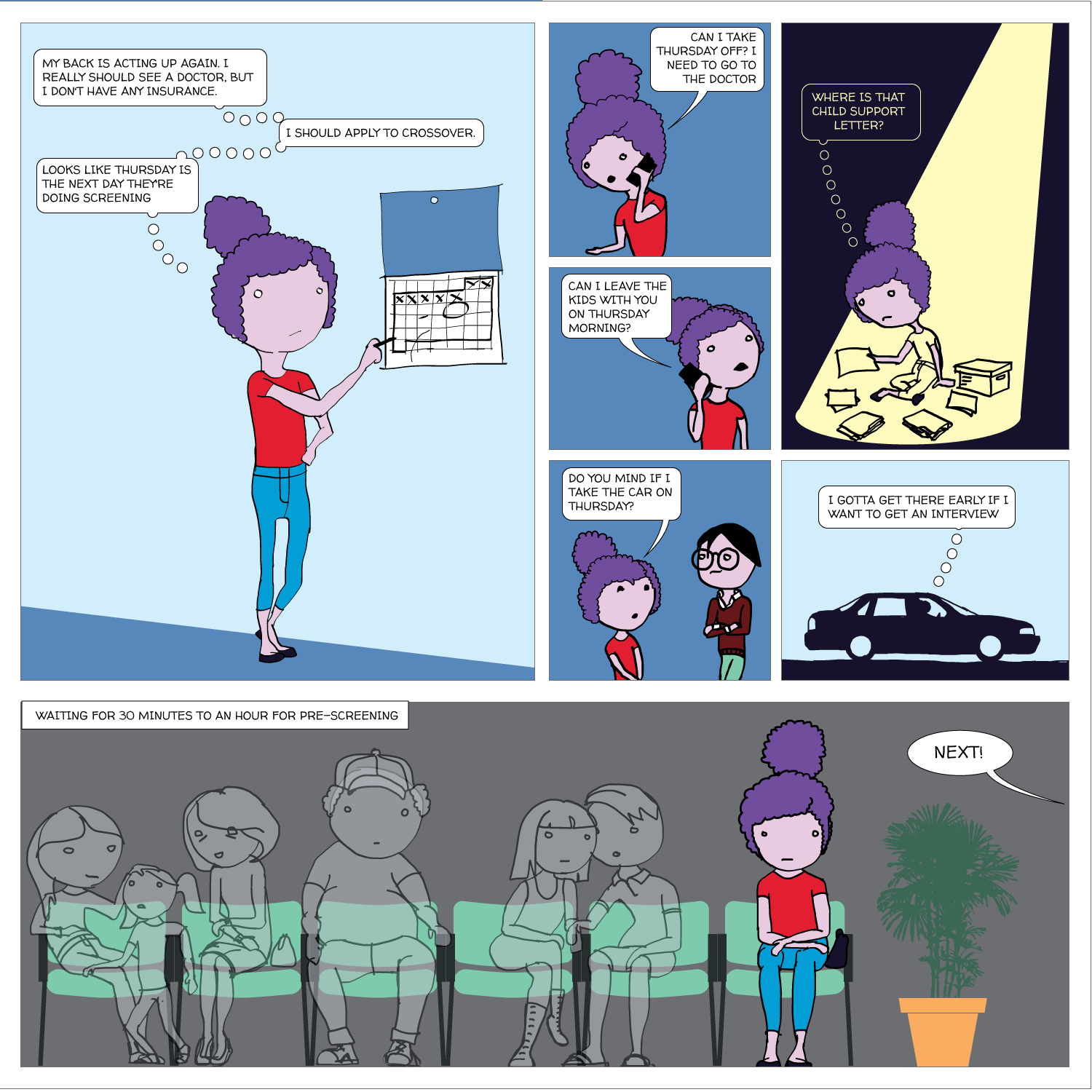

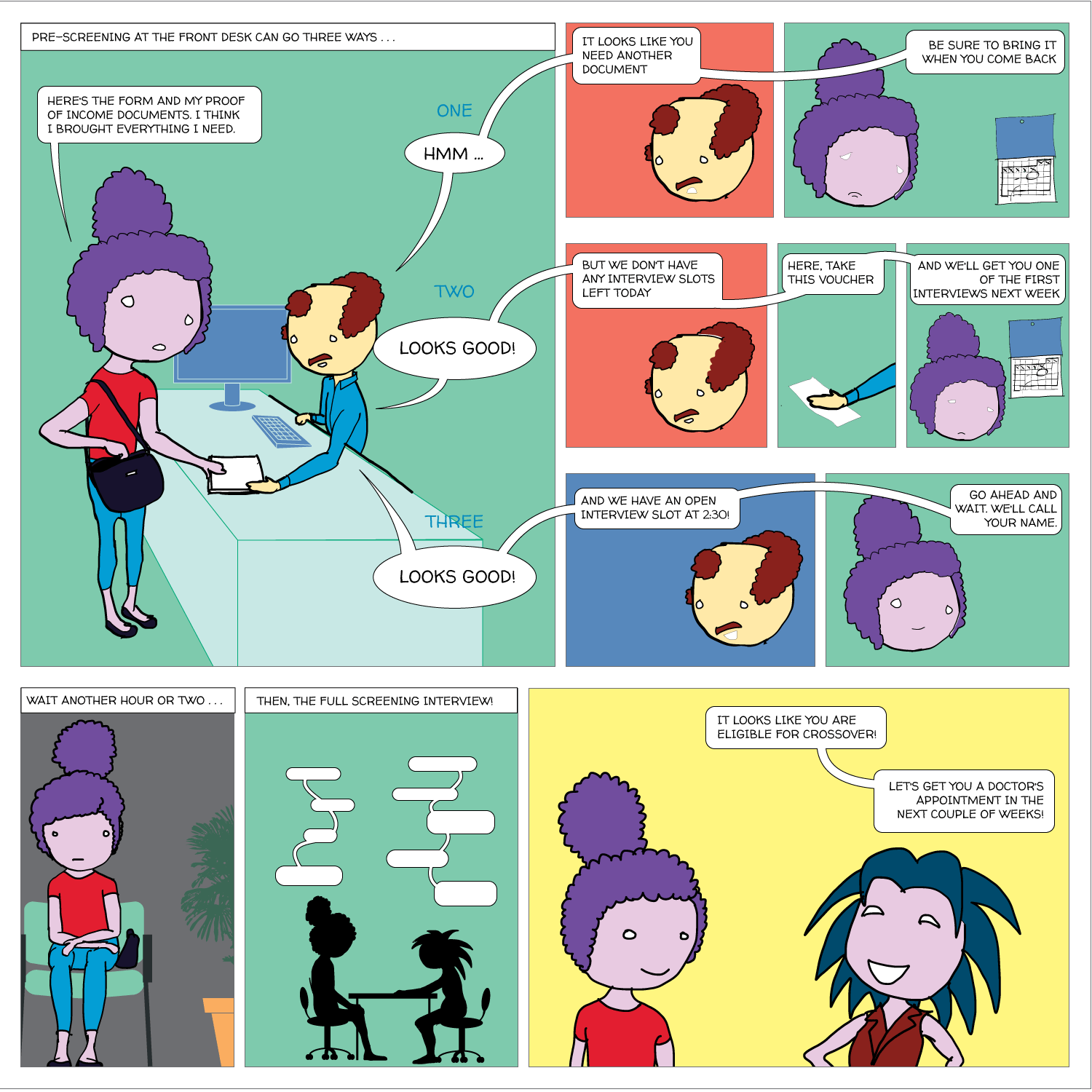

It can be slow and confusing. No two organizations screen in exactly the same way, but the process at a primary care clinic might look like this (click image for larger version):

It’s redundant. If patients visit another provider, they usually have to go through a separate screening, even though the applications ask for most of the same information. A few providers share a form, but most don’t. The following diagram illustrates one path a patient might take.

What this means

For care providers, the status quo means spending a great deal of staff time on screening that could otherwise be spent on something more directly related to patient care. For patients, it means delays getting into care (which can mean that the ED is a better option). The confusion and frustration also damages patients’ trust in the healthcare system. Community members told us that application processes are confusing, it’s hard to get accurate and complete information about eligibility, they don’t understand why their applications are rejected, and it’s demoralizing to have to prove low income again and again.

Goals

Our goals are:

- Decrease the amount of time it takes patients to get through the eligibility screening process.

- Increase patient trust and satisfaction.

Progress

Over the past few months, we built a prototype web application and started testing it with potential users in Richmond. This is what it looks like.

Online applications: Patients often start an application at a clinic but don’t have all the necessary documentation, so they have to return to the office another day--not always easy with limited transportation options. Our program has patient profiles containing the questions currently found on the paper application forms, and allows users to upload images of income proof documents like pay stubs. If all this information is filled out, it could replace the paper application for a patient. Ideally, patients could fill out their entire application at home or with a social worker or community health worker, and go to the office only for medical appointments.

Share screening data: Right now, patients who need care from more than one organization usually have to start the eligibility screening process from scratch at each one. Our application allows organizations to share a patient’s information so that she doesn’t have to provide it again. Initially, a patient’s information is only available to users at the organization that created the profile, but if that organization wants to refer the patient somewhere else, they can use this feature to make the profile available to the appropriate users.

What happens if a community health worker creates a record for a patient at one of the resource centers in the public housing communities, and the patient later shows up at a clinic, but without an explicit referral from the resource center? The clinic could contact the resource center and ask them to share the patient’s information, but that could take a while. This feature allows a clinic user to look up the patient by name and date of birth, but hides the rest of the patient’s information until the user confirms that she has the patient’s consent. After providing confirmation, the user can immediately access the information.

Was this address updated last week or two years ago? Who can I contact if I have questions about an application filled out elsewhere? What other organizations have screened this patient? This section tracks changes to each patient’s profile, allowing users to check when each piece of information was added and by whom.

Pre-screening: Because the process can be so long and frustrating, patients are sometimes reluctant to apply for services when they’re not sure if they’re likely to qualify. On the other hand, providers told us that patients sometimes wait hours for a financial screening, only to find out that they’re not eligible, and the providers spend significant time processing those applications. The pre-screening tool allows patients to answer the most basic eligibility questions and tells them whether they’re likely to qualify. It’s not a definitive answer, but it can help the patient figure out whether it’s worth the time to fill out a complete application, which could be up to 100 questions. We hope this will encourage patients who qualify to apply, and save both patients and providers time by discouraging applications from patients who definitely will not qualify.

Mobile version: The application also works on smartphones or tablets, so it can be used outside of offices. For example, community health workers could use it while visiting patients in their homes.

Universal screening form: Some service providers in Richmond have been discussing creating a universal screening form for years. This doesn’t necessarily need to be a technical project--simply using the same paper form for all applications would be a huge step forward. It’s challenging to reconcile the different needs and constraints of all the organizations, but we’re hopeful that our project can be a catalyst for more coordination.

Process

Research

A key part of Code for America’s approach is building with communities, not for them. During our initial research phase, we talked with over 100 people, including clinicians, social workers, community health workers, hospital and clinic administrators, technical staff at RCHD and the City of Richmond, academics, leaders at health-related nonprofits, and community members who use safety-net health services. We asked them about their experiences with safety-net health services in Richmond, their hopes and challenges, and how technology helps or hinders their work. We also spent several days shadowing social workers and community health workers.

Several themes emerged, which we discussed in our February blog post.

- It’s hard to keep track of all the available services, hard to figure out what you’re eligible for, and hard to apply.

- Appointment scheduling is complicated.

- Mental health is fundamental, but care is often difficult to access.

- For some, the ED is a better option than primary care.

- Service providers struggle to communicate with each other efficiently.

- Richmond’s community health advocate program has huge potential.

We decided to focus on eligibility screening for several reasons:

- Consistent feedback from patients, service providers, and navigators that a web application aimed at this process could help people get medical care faster and improve their experience with the health system.

- We haven’t found existing software that serves this purpose.

- The size of the project makes it feasible for three people to build in under a year.

As our focus has narrowed, we’ve met with many of the same people again to get their feedback on our progress and future directions. In April, we organized a brainstorm session that included eligibility screening staff from six organizations.

Development and User Testing

Despite all of our research, anything we build at this stage is based on our assumptions, both explicit and implicit, about what users want and need. Only those users can show us which are right and which are wrong, and we want to get that feedback early and often so that we can make sure what we build works for them. Our last two trips to Richmond focused on user research. This usually means showing our prototype application to potential users and letting them navigate through it without too much direction, asking them about their expectations and thoughts at each step.

We focused on people in three different roles.

- Screeners: the staff who review applications and determine whether a patient is eligible for care or where she falls on a sliding scale.

- Navigators: people who are not screeners, but help patients apply for health services. They include case managers and community health workers.

- Administrators: the leadership of the organizations involved. They probably won’t use the application frequently themselves, but they can give us feedback on whether the application fits their organization’s larger goals and meets their funders’ requirements.

Much of the user feedback focuses on user interface details. For example, it doesn’t make sense to ask about the spouse’s employment status if the patient isn’t married. Or maybe a dropdown for phone number type (home, cell, work, etc) would be easier to use than a text field. We want to fix these issues as quickly as possible to eliminate potential pain points. But most important are the big questions: What would you use this for? How could it help you meet your goals? What would prevent you from using the software today? What would make you want to start using it immediately?

Technical Tools

Our prototype is built with Python, Flask, and SQLAlchemy and hosted on Heroku. You can follow our coding progress on Github.

Side Projects

Searchable Services

The single most requested tool in our February meetings was an up-to-date, searchable list of all available services for low-income people in Richmond. Because services change so quickly, existing resources like the statewide 211 system tend to have incomplete or out of date information. Some case managers we met curated their own lists, but those are not publicly available.

Amber Haley and her team at the Center on Society and Health at VCU maintain a detailed Google Spreadsheet of resources in the city that includes services offered, contact information, and hours of operation. In March, we developed a searchable web-based list of services in Richmond that uses this spreadsheet as the database. This means that when she updates the spreadsheet, it automatically updates the website as well--no need to enter data into a separate system!

After building this prototype, we decided not to develop it as our main project because of the number of companies and nonprofits already working on this problem. The last thing we wanted to do was create yet another out of date list of resources (see this comic). Our current role in this project is to help our partners evaluate the existing software options.

Federal Poverty Level API

Since a patient’s eligibility is largely determined by his Federal Poverty Level percentage, our projects require calculating this number from the patient’s income and household size. The government adjusts the FPL formula annually, which means any software that performs this calculation has to be updated accordingly. To make this easier, we built the FPL API, which offloads the calculations to a single location that can be used by an unlimited number of projects. The code is open-source, so anyone can use it for their own application. We used this to build a lightweight calculator that staff can use to determine where a patient falls on the Virginia Department of Health’s sliding fee scale.

Brigade & Community Events

Code for America’s Brigade program is a network of local volunteer groups that work on civic technology projects. The Code for RVA Brigade began meeting in early 2014, and we’ve had the chance to be part of several of their events this year, including Code Across in February and National Day of Civic Hacking in June. Both events brought together government employees, local designers and programmers, and other civic-minded community members for a day of exploring ways technology can improve governments and communities. Projects included mapping local STI testing center locations and deploying a SNAP benefits pre-screeneing tool.

Next Steps

We will continue cycles of development and user testing over the next few months. Our goal is to finish the bulk of major feature development and begin testing with real patients by mid-August so that we can spend the remainder of the year refining the application based on feedback. Major areas of research and development moving forward include:

Application Questions

We're continuing to research which application questions to include and how to present them. Some questions on existing paper forms, like race and ethnicity, confused our testers—how can we ask this as clearly as possible? When one form asks for “people you are financially responsible for” and another asks for “people in household”, we want to combine those into a single question when possible, but need to make sure each organization gets the details their operations or funders require. Similarly, what information should a user be required to enter before submitting an application, and what is optional? These questions require ongoing conversations with our partners.

Translation

Richmond has a growing immigrant population, and the organizations we’re working with serve many patients who don’t speak English. We’re currently building a full translation feature into the app so that screeners or navigators can walk patients through the process in Spanish. We will demo the initial version at the Richmond Latino Health Summit on June 26th.

Analytics

The administrators of these organizations track a range of metrics to guide their work and show to funders. We’re working with them to figure out what data our application could export that would be helpful to them. For example, tracking the organizations that access each patient’s data could allow them to visualize the network of services their patients are using.

Avoiding double data entry

We need to avoid forcing users to enter data twice. At organizations where users currently enter eligibility data manually into an electronic health record (EHR) system, asking them to enter the same data into our application as well could mean adding lots of extra work. We’re experimenting with ways to avoid this problem—for example, by sharing data with existing software or emailing completed forms to some organizations rather than asking them to log in to the application.

HIPAA compliance

It’s crucial to ensure that all data sharing in our application is HIPAA-compliant. We’re researching ways to structure HIPAA agreements for patients and organizations that make everyone comfortable without adding more overhead than necessary.

Conclusion

We are excited to continue developing this project with our partners in Richmond. Many thanks to the following people for their support thus far:

Our funders and city partners; Ford Franklin, Rick Harris, Teresa Kimm, Maureen Neal, Kysha Washington (Daily Planet); Trina Jaehnigen, Velvet Mangum-Holmes, Beth Merchent, Sean O’Brien, Jameika Sampson, Tammy Toler, Kara Weiland (Bon Secours); John Baumann, Sarah Bennett, Sara Conlon (OAR); Camila Borja, Paulette Edwards, Sheryl Garland, Amber Haley, Barbara Harding, Kim Lewis, Kate Neuhausen, Ryan Raisig, Albert Walker (VCU); Julie Bilodeau, Alex Chamberlain, Lynn Williams (CrossOver); Veronica Blount, Sandy Bosher, Nicole Fields, Kimyatta Moses, Amy Popovich, Shikita Taylor (Richmond City Health District); Sanchita Dasgupta, Leslie Gibson, Marilyn Nicol, Elizabeth Wong (Access Now); Pamela Moore-Barr (Richmond Center for High Blood Pressure); Gwen Corley Creighton (Richmond Promise Neighborhood); Damon Jiggetts (Peter Paul Development Center); Sarah Scarbrough (Richmond City Sheriff's Office); Cynthia Newbille (Richmond City Council); Deepak Madala, Dana Wiggins (Virginia Poverty Law Center); Amelia Goldsmith (Central Virginia Legal Aid Society); Aneesh Chopra, Deven McGraw, and many more!